Cutting straight to the point, inflation is the measure of increase in the cost of living. It sounds a little subjective on the face of it, particularly for such an important economic gauge. What exactly constitutes the cost of living? Burgers? Moisturiser? Daffodils? The answer is the CPI, or Consumer Price Index. The CPI is a weighted basket of various products and services that serves as a benchmark for the costs of everyday life, such as food, taxes, transport, etc. Inflation is then calculated by comparing the current CPI number to the previous one, typically on a month-on-month or year-on-year basis. Either way, the figures are annualised, meaning that a 3% MoM inflation number equates to a monthly rate that would produce 3% yearly inflation if maintained for 12 months.

Any inflation figure above zero means that prices are going up. A negative inflation figure means that prices are in fact going down, a phenomenon known as deflation.

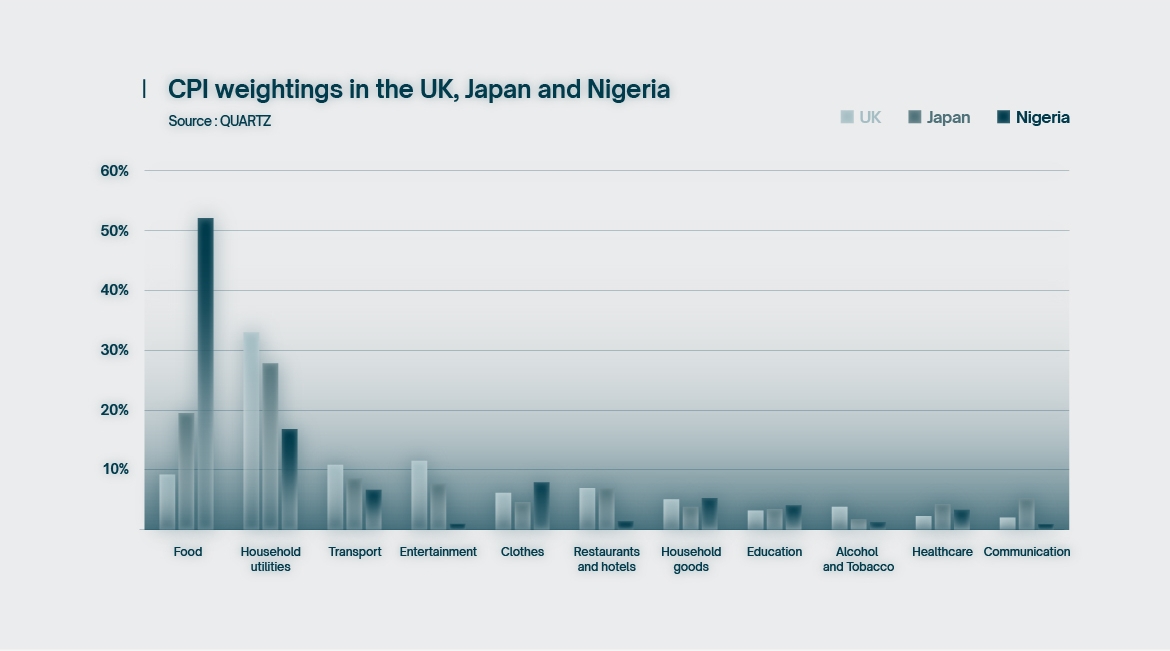

So it all boils down to the CPI basket. What makes the cut and what doesn’t? This is where things become less mathematical and a little more controversial. CPI is calculated differently in different countries. The weightings used in the UK are not the same as those used in Nigeria or Japan. Nor should they be – depending on the type of economy, a country’s people will have entirely different needs and concerns. Spending habits also change over time. For example, the internet, smartphones and streaming services have changed communication and entertainment expenditure considerably over the last ten years alone. For this reason, many countries rebalance their CPI weightings every year.

This is the first point of contention regarding the CPI. Detractors of the metric will claim that these rebalancing operations only serve to mask the true extent of price inflation over time, hiding just how much the cost of living has risen over the years, decades and generations.

The CPI includes the following categories: food, alcohol and tobacco, household utilities, household goods, clothes, transport, healthcare, communication, education, entertainment, restaurants and hotels. This is where the contentions continue. Critics of the CPI will be quick to point out the blinding absence of property prices in the index. There is an argument to be made that a house, while not exactly a consumable, still has its place as a cost-of-living expense, given that it is literally where people live. There have been a few attempts to include house prices among various inflation metrics, but none of them ever stuck.

The way different countries calculate their respective CPI figures reveals a lot about the spending habits of its people:

As shown above, for the average Nigerian, food prices account for over half of all spending. This is illustrative of a long-recognised rule of thumb in economics: the less developed a given economy, the greater the part of the household budget must be spent on food. In contrast, in more developed nations, utilities constitute the bulk of household expenditure. No matter what part of the world one finds themselves in however, food and energy make up a large part of people’s spending.

The rate described up until now is known as headline inflation, which includes all of the above categories. The problem is that due to their inherent volatility, food and energy prices can seasonally skew inflation figures, often painting an inaccurate picture of what’s going on behind the scenes. Oil prices can change drastically following geopolitical turmoil, food prices can be affected by weather and agricultural fluctuations. For this reason, a more refined metric was developed by economists, known as core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices. Core inflation is often presented side-by-side with headline inflation in economic news publications due to its ability to cut out distorting elements.

On the topic of economic news, how does inflation tend to affect financial markets? Inflation is hugely import because it falls directly within the remit of a country’s central bank. The central bank’s primary responsibility is to maintain monetary stability. Monetary stability implies a target inflation figure, typically in the ballpark of 2%. The central bank will look at the actual inflation data and adjust interest rates in an effort to nudge inflation in the right direction. High inflation will usually force the central bank to raise interest rates, curtailing spending and investment, hopefully leading to a reduction in price inflation. Low inflation will provoke the opposite response, causing the central bank to decrease rates, promoting financial activity and injecting markets with added liquidity. Inflation data therefore has a tremendous impact on markets at large.

It is worth addressing an aspect of inflation dialogue that frequently causes confusion. Headlines of “inflation going down” or “inflation on the rise” are commonplace. Inflation, as a metric, is a measure of rate of change, not change itself. Falling inflation does not necessarily mean that prices are falling, merely that the rate at which they are increasing is slowing down. Analogous with length and velocity, a car travelling along a road will still continue to cover more distance despite a reduced speed.

คำเตือนความเสี่ยง : การซื้อขายตราสารอนุพันธ์และผลิตภัณฑ์ที่มีเลเวอเรจมีความเสี่ยงสูง

เปิดบัญชี